Summary

This piece describes my experience trying speed reading. My final assessment is that while it can be fun and helpful to force yourself to read faster on occasion, I usually don't worry about my reading speed, because I think there's a pretty sharp tradeoff between speed and internalization of the material.

Contents

Introduction

When I was in high school, I was excessively perfectionist about school work. I felt I needed to understand every sentence of every assigned reading, and I wanted to reflect on each sentence to fully absorb its meaning. Unfortunately, this meant I took far longer than other students to get through an assignment, and too often I needed to stay up late to finish my homework despite having worked on it non-stop since school finished that day. Toward the end of 11th grade, I realized that my perfectionism was unsustainable, so I cut back without much impact to my academic performance.

Speed reading?

In 12th grade I decided to investigate speed reading, since I thought it would be useful to get through more material faster. I had only heard of speed reading twice before:

- In 4th grade, while I was writing a report on Jimmy Carter, a fellow student told me that Carter was a speed reader.

- A few years later, I heard a radio ad for a speed-reading course that promised to let you "polish off a novel in an afternoon".

When I looked up speed reading online, I was amazed by what I found. For instance, Evelyn Wood was said to be able to read 6000 words per minute. Because I had little experience with skepticism at the time, I took these claims mostly at face value and made it a goal for myself to read appreciably faster than I currently did.

For a cumulative total of many hours, I practiced speed reading. Sometimes I used a sliding bookmark that I pushed down a page to force myself to maintain a fast pace, while other times I just mentally required myself to push forward briskly. I mostly read at about 30 seconds per page on the book The Big Boys. I understood hardly any of it, but the speed-reading advice suggested to force speed first and let comprehension follow, so hoped that my understanding would improve with time.

I didn't keep objective measurements, so I can't tell if my speed did improve at all, but if it did, it probably wasn't by much. By the end of The Big Boys, I knew almost nothing of what it had said, apart from a few random lines that I had processed in isolation. Eventually I stopped my speed-reading practice, since I wasn't able to speed-read through anything important.

About a year later, I came across "The 1,000-Word Dash". Its subtitle summarizes its conclusion: "College-educated people who fret they read too slow should relax. Nobody reads much faster than 400 words per minute." This was indeed a relief to me, because I felt somewhat stupid for reading relatively slowly. The article debunks claims like those of Evelyn Wood about hyper-fast reading with excellent comprehension. An entry in the The Skeptic's Dictionary also challenges reports of astounding reading speeds.

Frank (2015) says: "Speed readers who claim that they can do any more than 400, maybe 500 words per minute tops, are doing so at a loss of comprehension. In general, reading at lower comprehension rates should be considered skimming. And that's what speed reading is—it's skimming."

Combating perfectionism

I think my average reading speed has increased somewhat since high school, but this probably has less to do with speed-reading training and more to do with my mindset: if I miss the understanding of a line or two out of a few paragraphs, I don't have to go back and figure them out, unless the document is very important. I'm now accustomed to browsing web pages for a few key sentences rather than needing to read the whole thing. The main reason for this is necessity: there's simply too much information out there. Also, because there's so much information, any given article feels cheap. I don't have to understand every last detail of it, because there's a virtual infinitude of other articles to read next.

Swarthmore College professor Timothy Burke has a helpful piece, "Staying Afloat: Some Scattered Suggestions on Reading in College", that argues in favor of skimming and reading selectively. The classic How to Read a Book makes similar points about actively extracting information from a book by seeking an outline before filling in details. In 2006, I attended a lecture in which a Swarthmore alumnus said that even though he reads slowly, he gets through a lot of material by figuring out the right parts of an article to read carefully. This is mostly how I read if I must skim: look for a few key passages and digest those.

I think school teaches reading wrong. When there's a specific list of assigned reading, students like me feel the sense that every word of every text on that list is important, and every other word is unimportant. But in the real world, there's more text available than you can ever read, so it's good to skip around, triage, read parts of articles without finishing them, and focus on getting what you came for rather than perfecting comprehension of one particular assigned article. Reading for a purpose is naturally more fun and effective than reading something that's required.

How much do you absorb?

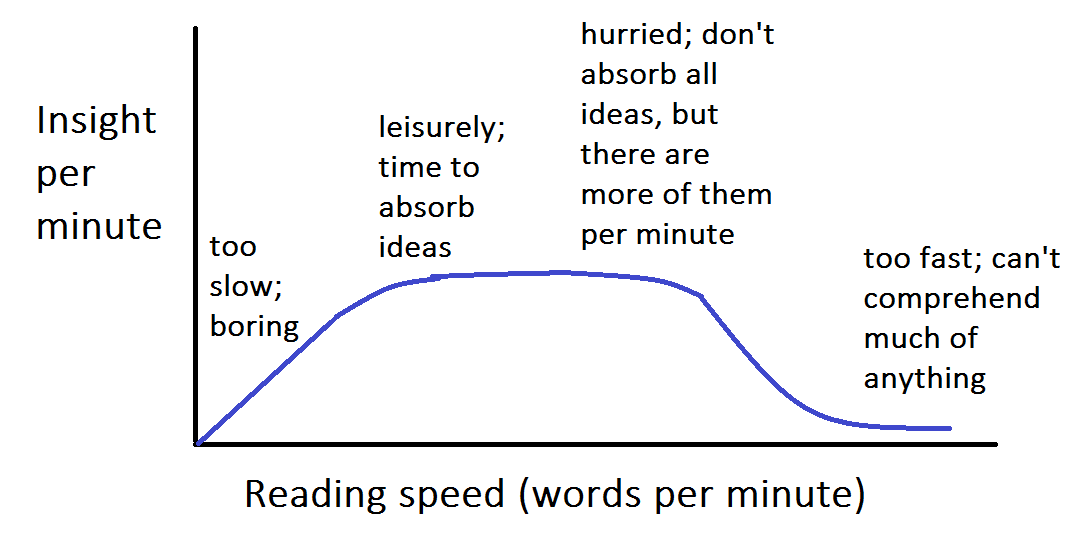

In my 10th-grade English class, each student was assigned a quotation and had to deliver a short speech analyzing it. One student got this saying: "It isn't just how many books you get through but how many books get through to you." Well, that saying certainly got through to me, because I often think back on it. I feel this is exactly the right philosophy on reading speed. If I'm reading something that's emotionally poignant or insight-dense, I ought to slow down so that I can fully absorb its content and build neural connections to other ideas. Progress in reading comes from how many new insights you have as a result. It's like digging for gold: you don't try to get through as much dirt as you can, but you instead slow down when you come to a densely concentrated gold patch.

One way to regard reading is as a stimulus to initiate thought about a topic, but if you rush through reading material, you don't leave yourself much time to actually have those thoughts.

I notice that when I read more slowly, each sentence has more impact on me. This is also true if I listen to text, which is typically a slower process than reading visually. In these cases, I have better retention, and my brain has more time to "connect the dots" to other things I know and thereby generate new ideas.

Imagine a high-school literature class in which students read a 100-word poem and then spend 20 minutes analyzing it through discussion. From a speed-reading perspective, this is hugely inefficient: the class is "reading" the poem at only 5 poem words per minute on average! But obviously the speed reader has an impoverished view of what reading is about.

Reading quickly is like drinking from a firehose, while reading slowly is like drinking from a water fountain: In either case, you're limited by your brain's processing and memory bandwidth, so you probably get roughly the same amount out of it in each case. Of course, this is only true up to a point. Reading too slowly could be more like drinking from a leaky faucet, with only a few drops of water per second.

I suspect it can be helpful to try challenging yourself to read faster every once in a while, if only to see what you're capable of and to stretch yourself. But most of the time I don't think about my reading speed. If I do, I tend to

- make myself more stressed

- become more self-conscious and thereby reduce comprehension

- enjoy the process less.

Like walking, reading is best done on auto-pilot without thinking about it. I read best by absorbing myself in the content of what I'm learning and losing track of the mechanics of the reading process.

I conjecture that most of the apparent gains from speed-reading training result from short-term increases in effort. It's hard to sustain a high speed in the long run. I've noticed the same when listening to audio content on my iPod, text-to-speech program, and YouTube, where I can adjust the speed up or down in an objectively measurable fashion. On my text-to-speech reader, I can still often mentally parse 3X text, but my ability to absorb it is limited, and the effort required is significant. I often end up listening at between 1X and 2X speed depending on how dense the content is. I never go beyond 2X because it's not sustainable in terms of the effort required (and because YouTube doesn't go beyond 2X). For some dense content I might prefer to listen at less than 1X speed.

I find that my reading speed can vary by maybe ~20 times depending on what I'm reading. If I'm browsing unimportant YouTube comments, I often breeze through them fairly quickly because the language and ideas they contain are simple and familiar, and I don't really care if I miss some of the points being made. In contrast, I often read technical material like tax forms or computer notifications extremely slowly, because the material is difficult, and making even a small mistake could be very bad. The fact that the appropriate reading speed can vary so dramatically is one reason I'm annoyed by articles that have estimated reading times. How quickly a given person reads something depends enormously on how difficult the material is, how much expertise the person has with the topic, and how alert the person is at a given moment. The other reason I find estimated reading times annoying is that even if the material is non-technical, I often prefer to read slowly because reading slowly is more fun and less stressful. The often absurdly short estimated reading times make me feel inferior for my life choice to be a slow reader.

"Speed-reading" Instagram?

Compare reading to another cognitive process: browsing through pictures, whether in a physical photo album or on Instagram. You can either browse through pictures quickly or slowly, and neither way of doing it is obviously better. It depends how much detail you want to absorb and what the emotional impact of the pictures is on you. While it feels subjectively like we can see everything in a photo at once, this is not the case, as the phenomenon of inattentional blindness shows. If you look at a picture longer, you'll see more of the objects it contains and have more thoughts about it. You can spend 10 minutes or more browsing through all the detailed events in a single Where's Waldo? image.

At an art museum, some people glance through paintings in rapid succession, while other people concentrate on a single painting for a long time. The latter people aren't "doing it wrong" and in need of courses on how to speed-browse art exhibits.

Reading can be similar, especially when lots of details are reported at once. Consider this sentence from a short story: "Next month she'd be eight feet high and glow like a lamp, or wear feathers and scales." In my experience, there are two ways to read sentences like this:

- Absorbing the words enough to create a mental picture of what's being described (including "glow like a lamp", "feathers", and "scales").

- Quickly gloss over the words, recognizing generally what they mean but without having time to create a mental picture of them.

These are two distinct levels of detail at which to absorb written text. In my experience, when reading quickly, you generally can't create rich mental images of what's being described. But mental images make the descriptions more powerful and lasting. So there does seem to be a genuine tradeoff between speed and depth of reading in cases like this.

Reading math

Math textbooks are one area where perfectionist reading may be justified. To do well in an advanced math course, you need to know basically every definition, most theorems, and at least the main proof strategies. The cumulative nature of the material doesn't work well with skimming.

When I was younger, if I read a mathematical claim, I would feel uneasy unless I also saw a proof of it. I felt as though I couldn't understand what was happening unless all steps were rigorously defended. For this reason, I much preferred the style of the math department over the physics department. Now I have a somewhat different viewpoint. I still greatly appreciate the ability to see a proof and absorb the insight that it offers. But I don't feel compelled to understand all proofs, partly because there are just too many theorems and too little time. There's value in being able to learn the high-level results of a mathematical field in order to get an overview, without understanding all the justifications.

A good analogy is with software. In theory it would be wonderful if I could read all the source code of all software programs I ever run. But time is short, and I can't do that. So most of the time I settle for working with the external interface of the program, perhaps coupled with some high-level overviews of how the software works under the hood. It's certainly very useful to read some real software source code to get a gist of how it works, but reading all source code isn't necessary. I can trust that other smart people have done enough of the work that I don't have to see everything for myself.

If I don't need to (or more likely, don't have time to) understand all the minutiae of a mathematical topic, I may read a mathematical paper as if it were an empirical study. In some sense, a theorem is a hypothesis that mathematicians have tested and found to be true. Thus, just reading theorems without understanding their proofs is no less rigorous than testing a result in the natural sciences without knowing its underlying mechanism.

I have greater appreciation for non-rigorous presentations of mathematical topics than I did when I was in college. The reason is that high-level intuitions can often be extremely useful, especially in domains like physics, economics, computer science, etc. where the mathematical results have real-world content that can be intuited directly. I think it's nobler to make sense of a mathematical result at a conceptual level than to wade unmotivatedly through the symbol manipulations of a proof, checking each step, but without absorbing the meaning of what's being done. Intuition is so important. It helps you avoid errors, look in the right directions, and apply what you're doing to relevant problems. Intuitions refined for a particular domain are often right and can be arrived at orders of magnitude faster than rigorous derivations.

A defense of perfectionist reading

As of 2017, I've reverted somewhat to my old perfectionist approach to learning, one manifestation of which is that I now sometimes read the entirety of articles I cite. I also try to look up all words I don't know, at least when reading about fields that are especially relevant to my work. These modi operandi are apparently common for researchers, as judging by some quotes from Pain (2016):

Cecilia Tubiana: Then I usually read the entire article from beginning to end [...].

Jeremy C. Borniger: If I want to delve deeper into the paper, I typically read it in its entirety and then also read a few of the previous papers from that group or other articles on the same topic. If there is a reference after a statement that I find particularly interesting or controversial, I also look it up. Should I need more detail, I access any provided data repositories or supplemental information. [...] I will typically pause immediately to look up things I don’t understand. The rest of the reading may not make sense if I don’t understand a key phrase or jargon. This can backfire a bit, though, as I often go down never-ending rabbit holes after looking something up (What is X? Oh, X influences Y. … So what’s Y? etc…). This can be sort of fun as you learn how everything is connected, but if you’re crunched for time this can pull your attention away from the task at hand.

Lachlan Gray: I usually start with the abstract, which gives me a brief snapshot of what the study is all about. Then I read the entire article, leaving the methods to the end unless I can't make sense of the results or I'm unfamiliar with the experiments.

That said, others disagree:

Rima Wilkes: It is important to realize that shortcuts have to be taken when reading papers so that there is time left to get our other work done, including writing, conducting research, attending meetings, teaching, and grading papers. Starting as a Ph.D. student, I have been reading the conclusions and methods of academic journal articles and chapters rather than entire books.

I personally enjoy going slower rather than faster. A verbalized explanation of why is that reading slowly is like eating slowly: You can digest the material steadily and make sure you haven't left a bunch of "crumbs" (points of understanding) that you either need to go back and pick up or leave behind. Emotionally, reading slowly also feels like eating slowly in a rather literal sense: if I read too much too quickly, I feel overstimulated, as though I've eaten too much sugar. It feels good but somehow bad at the same time.

There certainly is a point where being too obsessive about understanding everything is suboptimal in terms of learning if it means rereading every sentence multiple times. However, I don't think that reading slowly enough to process 99% of what's said is necessarily suboptimal, at least if you take a long-term view of learning in which the goal is to invest in understanding lots of things about the world, rather than just to complete a single task now. The brain can only think one substantive thought at a time, and the brain is usually occupied with thinking about something or other—even when you're not reading at all and are merely relaxing. Of course, some of those thoughts may be more useful than others. But as long as each thought you have per second while reading slowly is still useful, then I doubt reading slowly is much worse than reading quickly. When reading quickly, a different set of thoughts runs through your mind than when reading slowly, but those thoughts don't necessarily occur much faster, given the relatively tight constraints on the brain's rate of thinking. Even letting your mind wander during reading is not necessarily a bad thing; indeed, having your own thoughts sparked by what you're reading is part of the point of reading in the first place.

I picture reading slowly as like trying to get a 100% score in a video game, which involves completing all bonus levels, accomplishing all side quests, and collecting all items. In contrast, reading quickly is more like just getting to the final boss while leaving a lot of tasks undone. Some people prefer to play a lot of video games at a shallow level, whereas when I played video games in my childhood, I preferred to get 100% on a game before considering it finished. Some school homework, especially in literature-type courses where the volume of material is too much to absorb thoroughly, forces students to get to the end of the game quickly—i.e., to learn enough to complete whatever the assignment is, without doing all the bonus levels.

Shallow vs. deep thoughts

When I was a kid in the 1990s, adults bewailed the short attention spans of kids due to MTV. In the 2010s, the complaint is usually about smart phones and social media degrading our ability to focus. Based on my own observations, I suspect that such fears are overblown. But I do experience a temporary change in my expectations about the speed of content presentation after watching a music video versus after reading a "dry" text. Unlike the attention-span doomsayers, I don't think shorter attention spans are always worse (see Heffernan 2010); rather, it depends on what the goal is. Short attention spans are useful when getting an overview of a topic or a bunch of topics, without becoming mired in so much detail that you never make much progress. There's vastly more information accessible in our world than in the world of a rural farmer from the 1500s, so it makes sense that we sometimes need to browse quickly through lots of information.

At the same time, I think there is value in at least occasionally slowing down to make sure you fully absorb an idea and can make it your own. Introspectively, when I read rapidly or watch a fast-paced music video, my brain is mostly in a quick pattern-matching mode. The blur of images or words generates brief flashes of insight that mostly vanish within a second. This mode of information consumption works best for ideas that are familiar. It usually fails if your goal is to learn new ideas that require effort to grasp. Unless you're a genius, there's no shortcut around the more gradual and deliberate process of wrapping your brain around a new concept, which includes playing around with the idea in your head. This is why, for example, math and science courses use problem sets: they help students make the information their own by revisiting and manipulating the topics in new ways until students' brains become more facile with the content. Speed readers—even if they claim to have 100% comprehension—simply aren't doing the degree of cognitive work required to fully absorb, retain, and generate new insights based on what they're learning.

I also find that reading quickly—or doing tasks quickly in general—can put me in a careless mindset, where I'm not paying much attention to detail. While I'm a teetotaler and therefore can't say for sure, I find that reading too quickly can over time put me in a mental state that I imagine is similar to having had a few drinks: namely, my mind feels a bit "hazy", and I do tasks more sloppily. I imagine this is partly because going at a rapid pace has temporarily trained my brain to ignore details, which is what you have to do in order to read quickly. This mindset of "move fast and break things" is sometimes useful but sometimes very unwise. For example, before you click a link in an email, you should look carefully at the destination URL and other clues to make sure you don't fall for a phishing attack. (Or better yet, don't click links in emails at all, and instead go to the site on your own, even though this takes more time.) A person who speed-reads emails, browser warnings, and installer screens may end up with a malware-ridden computer.

Many things in life should not be done in a hurry. Getting in touch with your deepest moral values requires a calm, emotion-rich state of mind very different from the "caffeinated" state of mind you have when rushing through something. Making important decisions, working on hobbies, connecting with friends, and so on are best suited to a more relaxed pace. In general, there's so much more to life than the sheer number of words of text you process through your brain before you die.

Note-taking?

In school I was trained to take notes, during lectures and when reading textbooks.

One possible argument for note-taking is that it's a way to transfer information from teacher to student. However, the teacher could distribute the notes as a handout, without requiring students to write down the material themselves. A few of my teachers did this, and some of my college professors made their lecture slides available electronically.

I would guess that the bigger argument for note-taking is that it forces students to engage with the material rather than zoning out. However, just writing down information doesn't necessarily help in understanding it. As the saying goes: "College is a place where a professor's lecture notes go straight to the students' lecture notes, without passing through the brains of either." My experience with taking notes during lectures and especially fast-paced documentaries was that the process often reduced my understanding of the material because I was trying to pay attention to one stream of talking while simultaneously writing down a slightly different and slightly delayed stream of notes.

During high school, I created elaborate notebooks while reading my history textbooks. My notes contained basically all of the proper nouns in the textbooks, because basically all proper nouns in the textbooks were possible material for "Did You Read This?" quizzes in class the next day. This meant that my notebooks were sort of miniature versions of the textbook by the end of the year. Yet, after the course ended, I found that when I wanted to look something up, I went back to the original textbook rather than looking in my notes, both because the textbook had more comprehensive details and because I remembered where the material was in the textbook better than in my notebook. Textbooks also have nice tables of contents, indexes, and pictures to help locate information.

From 12th grade on, I never really took notes on things I read purely for the purpose of better absorbing or remembering the content. I find that per minute of studying time, I understand the material better just by reading it, playing around with the concepts, and doing sample problems, rather than writing down words that I can easily look up again in the text as needed. The only time I take notes is when I note to myself that I want to return to a passage from the text, perhaps to quote it or comment on it in an article I'm writing. I think underlining or drawing arrows can be useful when reading if you want to mark a given section of text as important, and most books I read on paper have markings throughout for this reason. But anything more time-consuming than this feels to me like wasted effort.

In the age of Google and Wikipedia, I find that organizing information for later review is usually unnecessary, because you can quickly look up most basic facts you might want to know, and other people have likely already summarized the material for you. (An exception would be a topic that isn't well known. I think it is quite useful to write notes/summaries that don't exist yet if they'll be shared on the web for the benefit of others.)

When I'm reading about a useful topic on the computer, I sometimes do "take notes" by copying the most useful quotes from the article into a text file for my future reference or if I need to act upon the information. These notes can be useful in cases where I wouldn't remember to look up the information otherwise or if I had to do a lot of digging to find the relevant information. Taking notes on something you can look up in 15 seconds is a waste, but taking notes on information that took you 15 minutes to find is worthwhile.